Image source: https://www.ias.edu/sites/default/files/styles/grid_feature_teaser/public/images/featured-thumbnails/ideas/Cover_TC-1.jpg?itok=elc3BUDK

This was a perfect introduction. And it's a story that did work. It did happen, and the machines are all around us. And it was a technology that was inevitable.

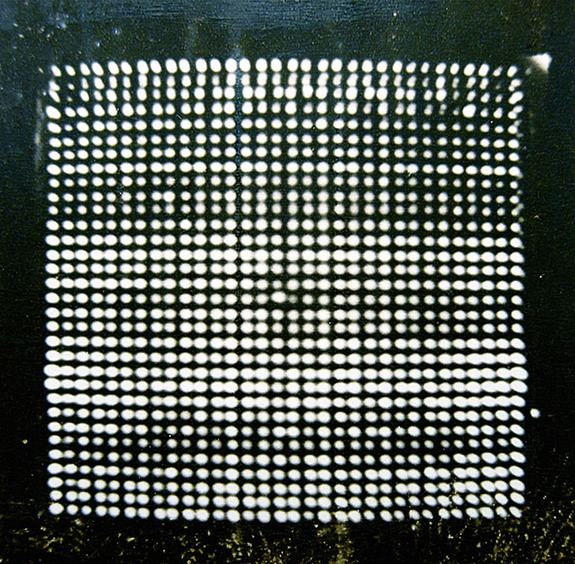

If the people I'm going to tell you the story about, if they hadn't done it, somebody else would have. So, it was sort of the right idea at the right time. This is Barricelli's universe. This is the universe we live in now.

It's the universe in which these machines are now doing all these things, including changing biology. I'm starting the story with the first atomic bomb at Trinity, which was the Manhattan Project. It was a little bit like TED: it brought a whole lot of very smart people together. And three of the smartest people were Stan Ulam, Richard Feynman and John von Neumann.

And it was Von Neumann who said, after the bomb, he was working on something much more important than bombs: he's thinking about computers. So, he wasn't only thinking about them; he built one. This is the machine he built. (Laughter) He built this machine, and we had a beautiful demonstration of how this thing really works, with these little bits.

And it's an idea that goes way back. The first person to really explain that was Thomas Hobbes, who, in 1651, explained how arithmetic and logic are the same thing, and if you want to do artificial thinking and artificial logic, you can do it all with arithmetic. He said you needed addition and subtraction. Leibniz, who came a little bit later -- this is 1679 -- showed that you didn't even need subtraction.

You could do the whole thing with addition. Here, we have all the binary arithmetic and logic that drove the computer revolution. And Leibniz was the first person to really talk about building such a machine. He talked about doing it with marbles, having gates and what we now call shift registers, where you shift the gates, drop the marbles down the tracks.

And that's what all these machines are doing, except, instead of doing it with marbles, they're doing it with electrons. And then we jump to Von Neumann, 1945, when he sort of reinvents the whole same thing. And 1945, after the war, the electronics existed to actually try and build such a machine. So June 1945 -- actually, the bomb hasn't even been dropped yet -- and Von Neumann is putting together all the theory to actually build this thing, which also goes back to Turing, who, before that, gave the idea that you could do all this with a very brainless, little, finite state machine, just reading a tape in and reading a tape out.

The other sort of genesis of what Von Neumann did was the difficulty of how you would predict the weather. Lewis Richardson saw how you could do this with a cellular array of people, giving them each a little chunk, and putting it together. Here, we have an electrical model illustrating a mind having a will, but capable of only two ideas. (Laughter) And that's really the simplest computer.

It's basically why you need the qubit, because it only has two ideas. And you put lots of those together, you get the essentials of the modern computer: the arithmetic unit, the central control, the memory, the recording medium, the input and the output. But, there's one catch. This is the fatal -- you know, we saw it in starting these programs up.

The instructions which govern this operation must be given in absolutely exhaustive detail. So, the programming has to be perfect, or it won't work. If you look at the origins of this, the classic history sort of takes it all back to the ENIAC here. But actually, the machine I'm going to tell you about, the Institute for Advanced Study machine, which is way up there, really should be down there.

So, I'm trying to revise history, and give some of these guys more credit than they've had. Such a computer would open up universes, which are, at the present, outside the range of any instruments. So it opens up a whole new world, and these people saw it. The guy who was supposed to build this machine was the guy in the middle, Vladimir Zworykin, from RCA.

RCA, in probably one of the lousiest business decisions of all time, decided not to go into computers. But the first meetings, November 1945, were at RCA's offices. RCA started this whole thing off, and said, you know, televisions are the future, not computers. The essentials were all there -- all the things that make these machines run.

Von Neumann, and a logician, and a mathematician from the army put this together. Then, they needed a place to build it. When RCA said no, that's when they decided to build it in Princeton, where Freeman works at the Institute. That's where I grew up as a kid.

That's me, that's my sister Esther, who's talked to you before, so we both go back to the birth of this thing. That's Freeman, a long time ago, and that was me. And this is Von Neumann and Morgenstern, who wrote the "Theory of Games." All these forces came together there, in Princeton. Oppenheimer, who had built the bomb.

The machine was actually used mainly for doing bomb calculations. And Julian Bigelow, who took Zworkykin's place as the engineer, to actually figure out, using electronics, how you would build this thing. The whole gang of people who came to work on this, and women in front, who actually did most of the coding, were the first programmers. These were the prototype geeks, the nerds.

They didn't fit in at the Institute. This is a letter from the director, concerned about -- "especially unfair on the matter of sugar." (Laughter) You can read the text. (Laughter) This is hackers getting in trouble for the first time. (Laughter).

These were not theoretical physicists. They were real soldering-gun type guys, and they actually built this thing. And we take it for granted now, that each of these machines has billions of transistors, doing billions of cycles per second without failing. They were using vacuum tubes, very narrow, sloppy techniques to get actually binary behavior out of these radio vacuum tubes.

They actually used 6J6, the common radio tube, because they found they were more reliable than the more expensive tubes. And what they did at the Institute was publish every step of the way. Reports were issued, so that this machine was cloned at 15 other places around the world. And it really was.

It was the original microprocessor. All the computers now are copies of that machine. The memory was in cathode ray tubes -- a whole bunch of spots on the face of the tube -- very, very sensitive to electromagnetic disturbances. So, there's 40 of these tubes, like a V-40 engine running the memory.

(Laughter) The input and the output was by teletype tape at first. This is a wire drive, using bicycle wheels. This is the archetype of the hard disk that's in your machine now. Then they switched to a magnetic drum.

This is modifying IBM equipment, which is the origins of the whole data-processing industry, later at IBM. And this is the beginning of computer graphics. The "Graph'g-Beam Turn On." This next slide, that's the -- as far as I know -- the first digital bitmap display, 1954. So, Von Neumann was already off in a theoretical cloud, doing abstract sorts of studies of how you could build reliable machines out of unreliable components.

Those guys drinking all the tea with sugar in it were writing in their logbooks, trying to get this thing to work, with all these 2,600 vacuum tubes that failed half the time. And that's what I've been doing, this last six months, is going through the logs. "Running time: two minutes. Input, output: 90 minutes." This includes a large amount of human error.

So they are always trying to figure out, what's machine error? What's human error? What's code, what's hardware? That's an engineer gazing at tube number 36, trying to figure out why the memory's not in focus. He had to focus the memory -- seems OK. So, he had to focus each tube just to get the memory up and running, let alone having, you know, software problems. "No use, went home." (Laughter) "Impossible to follow the damn thing, where's a directory?" So, already, they're complaining about the manuals: "before closing down in disgust ...

" "The General Arithmetic: Operating Logs." Burning lots of midnight oil. "MANIAC," which became the acronym for the machine, Mathematical and Numerical Integrator and Calculator, "lost its memory." "MANIAC regained its memory, when the power went off." "Machine or human?" "Aha!" So, they figured out it's a code problem. "Found trouble in code, I hope." "Code error, machine not guilty." "Damn it, I can be just as stubborn as this thing." (Laughter) "And the dawn came." So they ran all night. Twenty-four hours a day, this thing was running, mainly running bomb calculations.

"Everything up to this point is wasted time." "What's the use? Good night." "Master control off. The hell with it. Way off." (Laughter) "Something's wrong with the air conditioner -- smell of burning V-belts in the air." "A short -- do not turn the machine on." "IBM machine putting a tar-like substance on the cards. The tar is from the roof." So they really were working under tough conditions.

(Laughter) Here, "A mouse has climbed into the blower behind the regulator rack, set blower to vibrating. Result: no more mouse." (Laughter) "Here lies mouse. Born: ?. Died: 4:50 a.M., May 1953." (Laughter) There's an inside joke someone has penciled in: "Here lies Marston Mouse." If you're a mathematician, you get that, because Marston was a mathematician who objected to the computer being there.

"Picked a lightning bug off the drum." "Running at two kilocycles." That's two thousand cycles per second -- "yes, I'm chicken" -- so two kilocycles was slow speed. The high speed was 16 kilocycles. I don't know if you remember a Mac that was 16 Megahertz, that's slow speed. "I have now duplicated both results.

How will I know which is right, assuming one result is correct? This now is the third different output. I know when I'm licked." (Laughter) "We've duplicated errors before." "Machine run, fine. Code isn't." "Only happens when the machine is running." And sometimes things are okay. "Machine a thing of beauty, and a joy forever." "Perfect running." "Parting thought: when there's bigger and better errors, we'll have them." So, nobody was supposed to know they were actually designing bombs.

They're designing hydrogen bombs. But someone in the logbook, late one night, finally drew a bomb. So, that was the result. It was Mike, the first thermonuclear bomb, in 1952.

That was designed on that machine, in the woods behind the Institute. So Von Neumann invited a whole gang of weirdos from all over the world to work on all these problems. Barricelli, he came to do what we now call, really, artificial life, trying to see if, in this artificial universe -- he was a viral-geneticist, way, way, way ahead of his time. He's still ahead of some of the stuff that's being done now.

Trying to start an artificial genetic system running in the computer. Began -- his universe started March 3, '53. So it's almost exactly -- it's 50 years ago next Tuesday, I guess. And he saw everything in terms of -- he could read the binary code straight off the machine.

He had a wonderful rapport. Other people couldn't get the machine running. It always worked for him. Even errors were duplicated.

(Laughter) "Dr. Barricelli claims machine is wrong, code is right." So he designed this universe, and ran it. When the bomb people went home, he was allowed in there. He would run that thing all night long, running these things, if anybody remembers Stephen Wolfram, who reinvented this stuff.

And he published it. It wasn't locked up and disappeared. It was published in the literature. "If it's that easy to create living organisms, why not create a few yourself?" So, he decided to give it a try, to start this artificial biology going in the machines.

And he found all these, sort of -- it was like a naturalist coming in and looking at this tiny, 5,000-byte universe, and seeing all these things happening that we see in the outside world, in biology. This is some of the generations of his universe. But they're just going to stay numbers; they're not going to become organisms. They have to have something.

You have a genotype and you have to have a phenotype. They have to go out and do something. And he started doing that, started giving these little numerical organisms things they could play with -- playing chess with other machines and so on. And they did start to evolve.

And he went around the country after that. Every time there was a new, fast machine, he started using it, and saw exactly what's happening now. That the programs, instead of being turned off -- when you quit the program, you'd keep running and, basically, all the sorts of things like Windows is doing, running as a multi-cellular organism on many machines, he envisioned all that happening. And he saw that evolution itself was an intelligent process.

It wasn't any sort of creator intelligence, but the thing itself was a giant parallel computation that would have some intelligence. And he went out of his way to say that he was not saying this was lifelike, or a new kind of life. It just was another version of the same thing happening. And there's really no difference between what he was doing in the computer and what nature did billions of years ago.

And could you do it again now? So, when I went into these archives looking at this stuff, lo and behold, the archivist came up one day, saying, "I think we found another box that had been thrown out." And it was his universe on punch cards. So there it is, 50 years later, sitting there -- sort of suspended animation. That's the instructions for running -- this is actually the source code for one of those universes, with a note from the engineers saying they're having some problems. "There must be something about this code that you haven't explained yet." And I think that's really the truth.

We still don't understand how these very simple instructions can lead to increasing complexity. What's the dividing line between when that is lifelike and when it really is alive? These cards, now, thanks to me showing up, are being saved. And the question is, should we run them or not? You know, could we get them running? Do you want to let it loose on the Internet? These machines would think they -- these organisms, if they came back to life now -- whether they've died and gone to heaven, there's a universe. My laptop is 10 thousand million times the size of the universe that they lived in when Barricelli quit the project.

He was thinking far ahead, to how this would really grow into a new kind of life. And that's what's happening! When Juan Enriquez told us about these 12 trillion bits being transferred back and forth, of all this genomics data going to the proteomics lab, that's what Barricelli imagined: that this digital code in these machines is actually starting to code -- it already is coding from nucleic acids. We've been doing that since, you know, since we started PCR. And synthesizing small strings of DNA.

And real soon, we're actually going to be synthesizing the proteins, and, like Steve showed us, that just opens an entirely new world. It's a world that Von Neumann himself envisioned. This was published after he died: his sort of unfinished notes on self-reproducing machines, what it takes to get the machines sort of jump-started to where they begin to reproduce. It took really three people: Barricelli had the concept of the code as a living thing; Von Neumann saw how you could build the machines -- that now, last count, four million of these Von Neumann machines is built every 24 hours; and Julian Bigelow, who died 10 days ago -- this is John Markoff's obituary for him -- he was the important missing link, the engineer who came in and knew how to put those vacuum tubes together and make it work.

And all our computers have, inside them, the copies of the architecture that he had to just design one day, sort of on pencil and paper. And we owe a tremendous credit to that. And he explained, in a very generous way, the spirit that brought all these different people to the Institute for Advanced Study in the '40s to do this project, and make it freely available with no patents, no restrictions, no intellectual property disputes to the rest of the world. That's the last entry in the logbook when the machine was shut down, July 1958.

And it's Julian Bigelow who was running it until midnight when the machine was officially turned off. And that's the end. Thank you very much. (Applause).